Can a Wave Energy Park Serve as an Artificial Reef?

Artificial reefs are objects introduced into the ocean to provide habitat for sea creatures. From sunken ships to old busses, scientists have repurposed numerous types of hard surfaces dropped to the sea floor to provide habitat and increase biodiversity. Where previously only burrowing creatures could live, the introduction of an artificial reef creates an instant city that attracts fish, crustaceans, mollusks and others that prefer hard-walled homes. Such biodiversity is essential for ocean health. Some artificial reefs are beautiful to begin with, like the gallery of statues called Silent Evolution off the coast of Cancun; others begin as junk and are made beautiful by the life that grows on and around them, and by the patinas the saltwater gives them over time. And some artificial reefs can start their lives as wave energy parks.

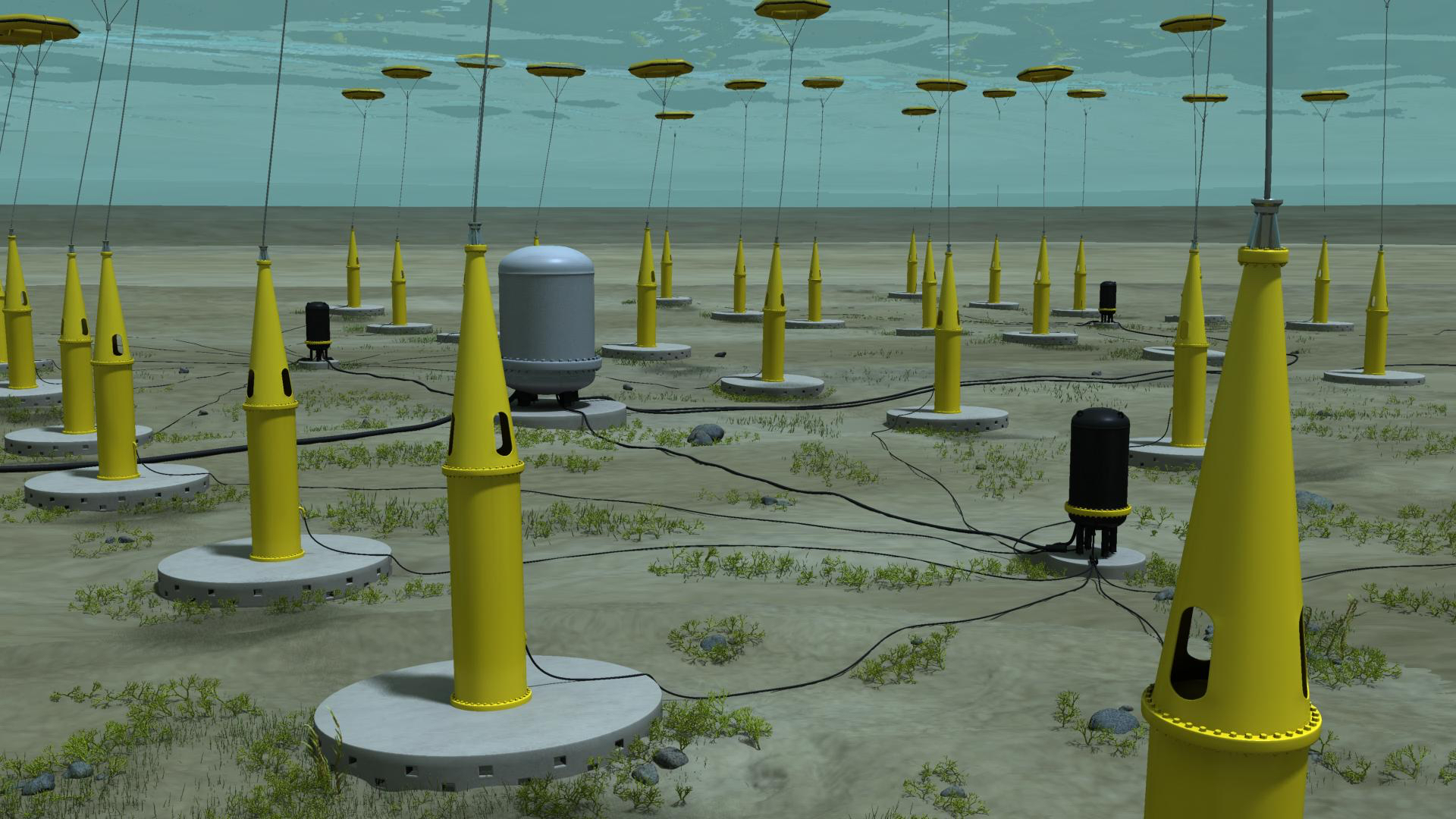

The question of whether marine energy installations could serve as artificial reefs has been studied for years. Several of those studies have been done in collaboration with Seabased, with wave energy parks built off the Swedish coast. In these parks near Sotenäs and Lysekil, gravity based linear generators – somewhat resembling large spark plugs with concrete bases – were installed at a depth of 25 or 50 meters. While folks at the surface celebrated the world’s first multi-generator grid-connected wave parks, scientists watched and took measurements to see what the environmental impact would be.

Coastal areas are often surrounded by barren sea floors of sand, clay, silt, or rock. That first three of these provide a stable base for Seabased’s wave energy converter (WEC) generators. They’re placed on the sea bottom and connected, with steel cables, to large buoys that sit on the surface, bobbing with the waves, creating motion in the generator on the seabed. This motion is vertical, without blades or turbines that could catch animals. From the generators, power is channeled to a marine substation which converts it into the proper electric voltage, sends it to a connection hub through subsea cable, and then on the electricity travels to a grid connection point.

Artist rendering of early Seabased wave energy park

UNDERWATER CITY FOR SEA CREATURES

The bases themselves are built of concrete, and it’s these concrete bases that scientists have experimented with. In one of the wave parks, scientists made holes of various sizes at different heights around the edges of the base creating a housing development, per se, for fish, crabs and other creatures that feel more secure living in a structure than under the sand. But once the wave parks are installed, with or without the bases with holes, it doesn’t really take long to get the neighbors interested.

“Whether they’re intentionally placed or arrive there by accident, artificial reefs usually settle quite quickly,” said Anke Bender, a PhD candidate in the department of Electrical Engineering at Uppsala University in Sweden who has been studying the artificial reef development around Seabased’s generators at Sotenäs for years. The ecological impact of the generators is her dissertation topic which is planned for release at the end of 2020. Within a few weeks of a reef structure appearing, sea animals discover the new real estate and start to move in.

Together with her professor, Jan Sundberg, who has a PhD in evolutionary theory, Bender and other scientists have tracked which species grew more abundant around the wave park and how they interacted with it. They were especially interested in how sea life that has commercial value responded. Since the loss of fishing area can be one of the objections that arise with wave installations, they wanted to see if the wave park itself could become a better habitat and breeding or spawning area than the seabed itself and would actually increase desirable populations and therefore, ultimately, help fishermen. They discovered that it could. Several species of fish and crabs had made the bases their home. Brown crabs found it especially appealing, and their numbers increased by more than 50%. But most exciting was the growth of the populations of Norway lobsters, which—in Lysekil—seemed to like burrowing under the edges of the generators. Also known as Dublin Bay prawn, langoustine or langostino, and scampi, these are Europe’s most important commercial crustacean. Once they settle into an area as juveniles, they stay there. So barring an event or fishing, their populations would increase. One year after the installation of the wave park, the lobsters had settled in and were twice as abundant inside the wave park as in the control area. By the second year after installation the numbers of all Norway lobsters in the area had nearly doubled. In that year, the numbers outside the park became roughly the same as those inside of it. In theory, the population growing in the park, protected from trawling and other fishing methods, could feed into a larger population in surrounding fishing areas.

Many other promising studies have been done using the wave parks, several by Olivia Langhamer, PhD, Analyst at the Unit Environmental Implementations and Enforcement at Swedish Agency for Marine and Water Management. Working with colleagues, she has studied Seabased generator bases placed at 25 meters deep at two locations near Lysekil, on the Swedish west coast. The studies included observations of sea life abundance, the effectiveness of the holes in increasing biodiversity, and the impact on populations that may be displaced by the generators. Some of the results of those studies indicated that populations of sea life increased months after the generators were deployed at one location, and fish and crabs were significantly more abundant on the foundations than in the surrounding soft bottoms. Three types of fish were observed using the holes, two of them cod. But many were seen around the foundations. Eight species of fish were recorded on the foundations, while only three species were noted in the control areas outside the wave park, indicating, perhaps, that the parks may contribute to biodiversity.

The scientists learned that each park ecosystem must be treated as unique to provide maximum benefit to the environment. “It’s really an exciting opportunity”, says Laurent Albert, CEO of Seabased. “Just as different birdhouses attract different birds, we look forward to working closely with scientists to tailor our wave energy parks to attract different species of marine life. The goal for Seabased is that each artificial reef will encourage a balanced ecosystem that is healthy both for the ocean and for desirable commercial species in exactly that area.”

THERE GOES THE NEIGHBORHOOD

The risk of increasing biodiversity is that you might attract species that don’t really belong in the area and that could mess up the ecosystem. As Bender noted, any time you introduce something new into an ecosystem, you can create problems. For example, the existence of the wave park seemed to possibly reduce the number of spiny starfish—perhaps because of an increased number of predators. While the bases provide habitat for some creatures, they also take up space that other species might have wanted to burrow into. They provide shelter for some species, but might interrupt the normal migration patterns (although not by much) of others. And then there are invasive species: species that wouldn’t have naturally lived in the area when it was just a sandy flat now find the place attractive. Species that are picked up to ballast a ship in one place are dropped off again in another, or carried in by tides and storms, and they can find the new housing development to their liking. Predators treat the environment like a new restaurant. All of this can be advantageous or challenging, depending on how it affects the balance of the ecosystem.

As of 2020, however, researchers at the Seabased installations did not find any invasive species.

CREATING A SAFE HAVEN

The other risks that come with putting a power installation into a natural environment include man-made ones. Using pile drivers to anchor the generators disturbs the ecosystem during construction; using toxic oils or paints or materials pollutes the water; having moving parts threatens wildlife; electromagnetism might impact the environment; and finally, there’s the noise of the generators hard at work. Fortunately, Seabased’s wave energy parks that can serve as artificial reefs don’t have any of these.

We just rest the generators on the sea floor without pile drivers. The generators don’t use oil and the paints used have been proven non-toxic in saltwater. There are no turbines or blades. The electromagnetic impact is slight, it extends only a meter from the subsea transmission cables. And while there is some noise, researchers have observed that the creatures don’t seem to even notice it.

The ocean is not one ecosystem. Around the world, each wave environment is unique, as are the communities around them. And any wave energy installation must work within local constraints and maximize local opportunities for creating clean energy, economic opportunities, jobs, and more. In the same way, each ocean ecosystem must be understood and helped to thrive and flourish with understanding and appreciation for its unique flora and fauna. And we’ll continue to explore ways to do that. Helping to protect the earth is part of our mission.